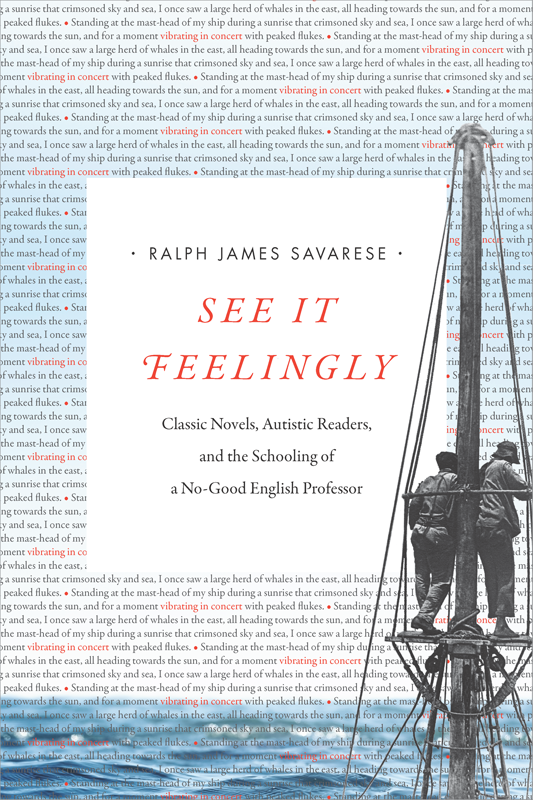

EndorsementsReviewsInterviewsOpinion Pieces & Excerpts

Praise for See It Feelingly

“See It Feelingly is a bold and astonishing act of crosscultural translation. By immersing the reader in what he beautifully terms ‘conjoined neurologies encountering the splendor of a classic book,’ Ralph James Savarese dismantles damaging myths about the limits of the autistic mind, while penetrating to the heart of how literature changes our lives.”

— Steve Silberman, author of NeuroTribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity

“This deft and impassioned hybrid—part memoir, part disability study, part portraiture, part literary criticism—is a book of revelations about reading, neurodiversity, and American literature. I was repeatedly startled by its slow cascade of correctives and insights—deepened, widened, and enlarged. It is a necessary book.”

— Edward Hirsch, author of How to Read a Poem: And Fall in Love with Poetry

“This compelling, thought-provoking book takes the reader on an intimate journey into the worlds of five autistic adults through their interpretation and response to classic literature. Drawing upon the neuroscience of autism and his own experience as a teacher and a father of an autistic son, Ralph James Savarese offers a powerful and hopeful perspective on autism, disability, and the value of diversity in humankind.”

— Geraldine Dawson, Director, Center for Autism and Brain Development, Duke University

“Finally, there is someone ‘outside’ my unusual world who cares deeply about autistic experience. Ralph James Savarese has avoided the typical human mistake of comfortable distance and, a true student of literature, immersed himself in the vibrant web of living lyricism where all things, including words, are not only equal, but one. I am so happy to have seen the birth of this work, not as a person on the spectrum, but as a primal poem.”

–Dawn Prince, author of Songs of the Gorilla Nation: My Journey through Autism

Reviews of See It Feelingly

Kirkus Reviews

A professor gains perspective into the minds of autistics by discussing literature. Savarese (English/Grinnell Univ.; Reasonable People: A Memoir of Autism and Adoption, 2007, etc.), a former neurohumanities fellow at Duke’s Institute for Brain Sciences, is the father of a nonspeaking autistic son, labeled as “low-functioning,” who has earned a 3.9 grade-point average at Oberlin College. Frustrated with such categories as high-functioning and low-functioning, as well as with assumptions about autistics’ intellectual and emotional capabilities, the author devised an investigation centered on reading. He knew that prominent researchers, such as Simon Baron-Cohen, hold that autistics are deficient in both theory of mind (“an awareness of what is in the mind of another person”) and “the apprehension of figurative language.” Those deficiencies should have impeded his autistic subjects from understanding and connecting with literary works. What Savarese discovered, however, were sensitive, responsive readers. In an impassioned and persuasive memoir of his interactions with autistics, he illuminates the diversity of their emotional, aesthetic, and intellectual experiences; the strategies that have enabled them to articulate their thoughts and communicate (even if they are nonspeaking); and their abiding desire to be recognized as fully functioning human beings with capacities that neurotypicals cannot imagine rather than sufferers from a “relentless pathology.” As the author’s son once remarked, “autism sucks, Dad, but I see things that you don’t see.” Focusing on American classics—including Moby-Dick, Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony, and Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?—Savarese discovered remarkable evidence of empathic connections, contradicting “perhaps the most destructive and defining idea about autism spectrum disorders”: autistics’ lack of empathy, which “is very much responsible for the stereotype of unfeeling aloneness.” Although three individuals he read with “shared certain challenges with speech,” the challenges were “as different as the way their sensory systems worked or the way they thought.” While the prevalent concept of an autism spectrum “is unfortunately linear and static,” Savarese underscores the need to revise such limiting perceptions. A fresh and absorbing examination of autism.

Wordgathering: Review by Michael Northen

What do Temple Grandin and The Curious Case of the Dog in the Nighttime have in common? Both of them have helped shape the public perception that people on the autism spectrum are unable to relate to the emotions of others? Mark Haddon’s book might be dismissed in the same stroke as organizations like Autism Speaks by saying that that these are not the authentic voices of people on the spectrum. But what about Grandin, perhaps the most celebrated example of an autistic person who has succeeded in society today? When she asserts that social and personal relationships mean nothing to her, how can we not believe her? This is the perceptual fortress that Ralph James Savarese attempts to assault in his new book See It Feelingly.

See It Feelingly, subtitled “Classic Novels, Autistic Readers, and the Schooling of a No-Good English Professor” is Savarese’s account of his efforts to confirm his proposal that readers on the autism spectrum can, in fact, enjoy literature through the reading of classic novels. Savarese certainly has the credentials. Not only has he written widely on autism, received numerous awards, and taught English literature at Grinnel College for years, but his own son, DJ Savarese is the first student on the autism spectrum to graduate from Oberlin College. As one might suspect, Ralph Savarese’s initial impulse to challenge the premise that people with autism function in “an obdurate, self-contained literality” originates with his own experiences with son, but numerous online blogs by autistic writers add credibility to that challenge.

The core of the book recounts Savarese work with five autistic adult readers. They range from his people of his acquaintance Tito Mukopadhyay and Jamie Burke, to Eugenie Belkin and Dora Raymaker whom he met only when beginning the project to Temple Grandin herself. In each case Savarese chose a literary work that he believed would mesh with the readers interests and reading habits. Functioning as an ethnographer, he is quick to note that despite the overall confirmation of his position, he made a number of false starts and assumptions himself in the process — hence the book’s subtitle.

In setting up the project, several factors played into Savarese’s decision to hold the reading sessions through Skype. One was the geographical distance between himself and some of his readers, but of at least equal importance is that it was a conducive medium to readers who, like Tito, do not speak. Having gained experience in working with autistic people over the years, Savarese also knew that working in unfamiliar environments tends to ratchet up anxiety levels and that working in their own home environment allowed them to relax. The use of Skype helped to create those conditions.

Perhaps what is most remarkable about See It Feelingly is the uniqueness of each of the reading experiences that the book describes. Part of this, is the varied nature of the novels that they read: Tito — Moby Dick, Jamie — Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony, Dora — Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? and Eugenie — Carson McCuller’s classic The Heart is the Lonely Hunter. Even accounting for the diverse nature of the texts, however, each reader’s mentorship unfolded in a unique fashion and, in the processes reveals alternative ways of approaching and valuing literature. If there is one thing that the readers have in common it is that, like the Duke of Gloucester in King Lear from which the book’s title is taken, they “See It Feelingly.” Each of the readers of these four novels strongly identified with the experiences of a character in the text on an emotional level.

The reader that Savarese leads off with is Tito Mukopadhyay. Tito, who has receive a fair amount of media attention, may be the person other than Temple Grandin with whom readers are be most familiar. As the author of The Mind Tree and other books describing his experiences as a non-speaking person on the autism spectrum, he is known for his inventive metaphors and non-traditional descriptions. He is also extremely involved in sensory experiences, particularly olfactory ones, which he brings to bear in his reading of Moby Dick. Tito identifies not with Ishmael, Ahab or any of the human characters but with the white whale itself. For Tito, the novel is an allegory of living with autism in a world where he is unique. He sees the land as the terrain of neurotypicals where he is unable to function and the ocean of autism in which he is continually being hunted down. Savarese’s account is made more powerful by the inclusion of Tito’s own words:

The Moby Dick of disorders swims within you. No see-saw can be as intense as the see-saw of hyper-and hyposensitivity, rocking you from one end to the other, lifting you up, dropping you down, then lifting you up again�throughout the ocean of days, months and years that we call life.

As he describes Tito’s interpretation Moby Dick, Savarese also provides contexts for picturing and understanding what is occurring. He describes Tito’s past history as well as his personal association with Tito. In the present tense he describes Tito’s difficulty in sitting down to Skype for even an hour and his need to run around the room flapping his arms to relieve the anxiety. While Savarese’s description of reading with Tito may be the lengthiest of the book, it also provides a sort of template for the way that the remaining chapters of the book work as well. Along the way, he integrates his interpretation of findings from neurology that bear on what he is witnessing.

An interesting contrast to the Tito chapter (“From a World as Fluid as the Sea”) is Dora Raymaker’s reading of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Unlike the situation just described, Savarese did not know Dora personally before contacting her to take part in the project. Like Tito, Dora is also an author — in her case of a cyberpunk novel — but unlike Tito she functions independently in the community having worked as a computer programmer and, at the time of her mentorship with Savarese, as a community-based researcher. She loved Blade Runner, the movie version of Dick’s novel (she’d seen it twenty-five times!), but was reluctant to tackle it as a book. Her reasons were understandable because she had difficulty accessing and sequencing words and, as Savarese writes, she thought “in visual spatial landscapes and need[ed] to consciously translate [her] thinking into language.”

As even the most ardent Philip K. Dick fans know, his strength is in his ability to create questions about the nature of reality, and most definitely not in his skill at visual description. Consequently, much of his writing — particularly at the books beginning — was opaque to Dora. Like Tito, though, Dora also became attached to one of the characters — Rachel Rosen, an android. In Dick’s novel, rather like the whale in Moby Dick, androids are to be hunted down and killed. Because Rachel is to all outward appearances, human, a test is devised that allows bounty hunters to indentify her as android. It is called the Voigt-Kampff and based on the premise that androids are unable to empathize with others. Sound familiar? Dora became deeply engaged in the novel.

Given her reputation for emotional detachment, Savarese saves the account of his work with Temple Grandin until last, priming readers to accept the book’s thesis by establishing that Tito, Dora, Jamie, and Eugenia are able to engage in literary novels. In books such as her influential Thinking in Pictures Grandin compares her mind to a computer’s search engine and she has made public statements as “The part of other people that has emotional relationships is not part of me.” Savarese knew that confirming his own beliefs about autism and literature would be challenging in these sessions, but was encouraged that Grandin herself was game to take part in his project. Knowing that she had difficulty with being able to remember narrative sequences, Savarese opted to have her read two short fiction pieces rather than attempt a novel. As with the other readers, he chose pieces that he felt might evoke an emotional response based upon background and interests, one dealing with animals and the other with a scientist who works alone.

Savarese’s report of his reading with Grandin is a fascinating one in which he faces frustration but also ultimately feels vindication. In the process, he acknowledges the ableism resident in his own neuruotypical thinking and the need to make adjustments.

Toward the beginning of the book, Savarese states:

My intention from the beginning of this project has been to eschew the customary focus on autistic deficits and to explore instead how a talent for sensory engagement—and, yes, strong feeling—might contribute productively to the reading process. If my son and other autistic people have taught me anything, it is to look for competence in unexpected forms.

See It Feelingly accomplishes this goal and much, much more. Whether or not one agrees with all that Savarese has to say, this is a powerful book — one that really must be experienced. It is a book that unlocks doors to the many rooms of autism and is likely to surprise the thinking of anyone who steps into them. It carries within it the possibilities of new perspectives on literary work, a greater understanding of autistic neurology, and the chance to meet some remarkable individuals. Read it.

Thinking Person’s Guide to Autism: Review by Maxfield Sparrow

Reading See it Feelingly took me much longer than I expected, because I wanted to stop to take notes with almost every page turn. Dr. Savarese has produced a masterpiece, simultaneously dense and accessible. His voice moves freely—alternating among lyrical, narrative, and instructive—never losing the flow, never dipping into pedantry, never soaring too far toward the abstract for the reader to follow. Not only is this collection of essays brimming with the most important information and ideas about autism, it is a collaboration of rare beauty.

See it Feelingly crosses genres effortlessly. The result is a book rich in the neuroscience of autism, literary criticism, Autistic poetry, the science and politics of neurodiversity, theory and practice of inclusive education, and direct quotes from Autists. See it Feelingly also belongs on my virtual bookshelf of Autistic Poetics*, along with Autistic Disturbances: Theorizing Autistic Poetics from the DSM to Robinson Crusoe, by Julia M. Rodas, and Authoring Autism: On Rhetoric and Neurological Queerness, by Melanie Yergeau. While Savarese, unlike Rodas and Yergeau, is not Autistic, his work that has culminated in See it Feelingly has given him great depth of insight into Autistic poetics. More importantly, his understanding of Autistic poetics is directly informed by the extensive conversations and feedback from his Autistic friends with whom he explores literary works.

There are six Autistic co-readers highlighted in See it Feelingly. Dr. Savarese makes it clear that he considers the relationships between his Autistic friends and himself to be more about shared journeys as equals than a hierarchical teacher-student relationship. One reason for this attitude was that his Autistic friends were teaching him as much, if not more than, he was teaching them. And they weren’t the stereotypically expected sort of lessons about autism and Autistics. Rather, his co-readers were teaching him new ways of engaging with the text—Autistic ways of reading. As Savarese writes on page 54,

“What literature professors call ‘close reading’ might as well be called ‘autistic reading,’ I decided, for the kind of careful attention and full-bodied engagement that Tito evinced are exactly what literature deserves.”

Savarese returns often to the theme of embodiment in writing and reading—“feelingly seeing” the text. He shows the deeply somatic (body/sensory as opposed to mind-based) nature of Autistic experience by weaving together three information strands: conversations in which various of his six co-readers share experiences of how they interact with the texts they are reading and discussing; explanations of some of the differences in brain structures and functions that cause Autistic people to engage somatic regions of our brains more actively and with more connections than non-autistic people; and a review of somatic theories in linguistics and poetics, suggesting that the sounds of language evolved as echoes of body movements. “Metric feet” in poetry echo the way language echoes the footfalls of running.

The six Autistic people Dr. Savarese explored literature with were: his son, DJ Savarese; Tito Rajarshi Mukhopadhyay; Jamie Burke; Dora Raymaker; Eugenie; and Temple Grandin. As Savarese notes in the introduction, what he has done is not a scientific study or even a random sample. The people he worked with were the people he knew one way or another. Or, as in Grandin’s case, people both famous and somewhat accessible. The choice to include Grandin also stemmed from the irresistible challenge of re-visiting Dr. Oliver Sacks’ assessment of Grandin’s assumed deficit with respect to literature in his book, An Anthropologist on Mars.

Dr. Savarese chose the books he read with each of his friends. The chapter about reading with his son is labeled prologue rather than chapter one. I think that choice is meant to show how DJ wasn’t just another Autistic to read with but The Autistic who taught Dr. Savarese his first lessons in full-autistic-body reading, re-living personal trauma while reading fictional trauma, close-autistic-reading, and the importance of building a raft of safety upon which to navigate the often treacherous waters of literature. Savarese focused mainly on a shared reading of Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. In chapter one, Savarese immersed in a slow—two chapters at a time—reading of Herman Melville’s classic, Moby Dick, with Mukhopadhyay. In chapter two, Savarese and Burke explore a classic Native American novel that plays with concepts of time, space, and ritual: Ceremony by Leslie Marmon Silko.

Chapter three spends a lot of time exploring the connections between the science fiction genre and autism, drawing heavily on Steve Silberman’s autism history, NeuroTribes. Savarese chose the novel before the reading partner in the case of Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?. After exploring the parallels between Vulcans (Spock) and androids (Data) and Autistics (as well as dipping into the reasons so many Autistics love Star Trek), Savarese knew he wanted to discuss Dick’s novel about a bounty hunter searching for renegade replicants with an Autistic reader. He chose Raymaker because he had been impressed by things she had said in the documentary film LovingLampposts, Living Autistic. Blade Runner was one of her favorite movies but she had not yet read the book upon which it was based.

In chapter four Dr. Savarese reads with a woman who chooses to go only by the name Eugenie. She is Autistic, Deaf, a classical ballerina and a figure skating choreographer. She already faces so many barriers as a multi-racial, Jewish, Deaf choreographer that she does what she can to keep her autism undercover, fearing it would tip the balance for too many people, rendering her unhirable. Together, they read The Heart is a Lonely Hunter by Carson McCullers. Savarese chose that novel as a fertile ground for exploring intersectionality—the synergy that happens when someone has more than one minority identity—in Eugenie’s case, the intersection of being multi-racial and multiply-disabled.

Finally, in chapter five, Dr. Savarese successfully deconstructs Dr. Sacks’ earlier assessment of Grandin during a shared reading of two short stories from the anthology Among Animals: The Lives of Animals and Humans in Contemporary Short Fiction: “Meat” and “The Ecstatic Cry.” Citing much of what has been said by and about Grandin to support the notion that she is purely logical with only the simplest emotions—he quotes Grandin on page 157, saying, “ [I] only understand . . . fear, anger, happiness, and sadness”—Savarese set out to explore Grandin’s actual emotional landscape through discussing literature together.

While Grandin’s initial response to “Meat” was frustration that the story never revealed what species of animal was described, I shed genuine tears reading just one excerpted paragraph Savarese included. Still, Savarese found great depth of reflection and insight in Grandin’s approach to the texts. Her literary reality was much richer than Savarese, or I, had been led to believe. When Savarese asked Grandin on page 171 if “Meat” had moved her, she replied, “Well, I don’t get overly emotional […] [b]ut the words created images in my head, and they moved me.” But Savarese was most insightful halfway through his recounting of their discussion of “The Ecstatic Cry” when he suddenly realized that he was trying to box Grandin up and force her into a mold every bit as much as he felt Sacks had done. Savarese writes, “Can we presume competence without striving for normalcy? I think so, but in my quest to uncover emotion, I was certainly muddying the waters.” (182)

In the epilogue, Dr. Savarese revisits theories of literature and reading but soon turns to pondering our future, based on the current grim political landscape in the U.S. He closes with a quote from Azar Nafisi, an Iranian professor, explaining that literature does not, “merely reflect reality but reveal a spectrum of truths, thus intrinsically going against the grain of totalitarian mindsets.” (195) Echoing her language, Savarese calls upon “a spectrum of readerly minds” to “stretch and amplify” the spectrum of truths. Now, more than ever, the world needs literature. And Dr. Savarese has amply demonstrated how much literature needs Autistics.

See it Feelingly is a manifesto of power, singing out the value and beauty of Autistic minds and lives. It centers non-speaking Autistics while expressing acceptance and inclusion for all flavors of Autists. It does not position our worth in the commercial sense we’re so accustomed to. Some of the co-readers have successful careers; others may never support themselves through labor and earned income. That is not where any of their value as human beings resides and Savarese makes that abundantly clear as he invites us to savor the inner lives of his friends. Literature is about what makes us human and Dr. Savarese and his friends find the humanity in fictional humans … and whales and penguins … by looking into the mirror of literature and seeing themselves reflected there in myriad forms. The careful reader—of any neurology—will look into See it Feelingly and find themselves reflected there as well.

Interviews with the Author

Wordgathering: Interview

Ralph James Savarese, author of See It Feelingly: Classic Novels, Autistic Readers, and the Schooling of a No-Good English Professor, was interviewed by Michael Northen. The book will be published by Duke University Press on October 12, 2018. Read interview here.

Inside Higher Ed: Interview

Professor Ralph James Savarese discusses with Inside Higher Ed his new book on insights gained from reading classic literature with people with autism. Read interview here.

Psychology Today: Interview

In his new book See It Feelingly: Classic Novels, Autistic Readers, and the Schooling of a No-Good English Professor, Ralph James Savarese chronicles his collaborations with several autistic readers, exploring classic American fiction. I was riveted by Savarese’s book—both the elegant writing and the procession of deeply humane insights. So I was delighted when he agreed to an interview, on topics ranging from literature’s transformative capacities, getting schooled by Temple Grandin, autism research, and Moby-Dick. Read interview here.

Opinion Pieces & Excerpts by the Author

From Salon: Reading fiction with Temple Grandin: Yes, people with autism can understand literature

It’s early in the 21st century, and we still have no idea what autistic people can do. Raising an autistic son who publishes poetry and creative nonfiction taught me that autism doesn’t have to be an impediment to literary understanding. To the contrary, it can even be a boon. My experience discussing fiction with people across the spectrum has only strengthened this belief. Read full article here.